Rideout is a culturally significant arts and criminal justice organisation based in Stoke on Trent. Established in 1999 by Saul Hewish and Chris Johnston, Rideout delivers theatre projects in prison and probation settings, and undertakes distinctive interdisciplinary creative collaborations in its work. The company has worked across theatre, music, sculpture, and film; as well as history, psychology, and architecture. Alongside prison-bound work, Rideout have also sought to engage the general public in discussion about the form and function of the criminal justice system.

Part of the project has been a collaboration with The Bristol Theatre Collection, who now house The Rideout Archive. Myself and Hewish collaborated with Heather Romaine, Nigel Bryant, and other archivists based at the Theatre Collection as they catalogued and digitised the material.

This work has led me to think about lots of things, but in this paper today, I am going to talk about the complex ‘afterlives’ at play when producing a prison arts archive. I think my central question is: Can a prison arts archive ever function as a form of, what Michelle Caswell calls, ‘liberatory memory work’?

Carceral Archives and Material Traces

The state uses surveillance, documentation and record keeping as strategies to oppress and dispossess citizens, particularly people from minoritised communities. Critical archival studies scholar Tonia Sutherland conceptualises the material collected through these processes of surveillance as carceral archives. These documents include things such as court transcripts, healthcare or social care records, school records, media reports, and – increasingly – social media documentation. Sutherland posits that carceral archives are materials animated by the State to codify particular practices, individuals and communities as risky or dangerous. Producing an archive of prison arts practice then invites a consideration of the kinds of material that arts organisations use to produce histories of their work and the ways in which this material might intersect or challenge carceral archives.

A significant proportion of the material that remains from Rideout projects across their 25 year history exists because of a desire within the company to share creative work across the prison boundary. That is, much of the material held in the archive was originally produced to:

- enable participants to have something tangible to remember the experience of a creative project and to share their artistry with their family or friends on the outside

- Enable the company to share creative work happening on the inside with a general public who cannot see it, and so potentially shift expectations of incarcerated people

Documentation of projects includes things like: CDs of music created, DVDs of films, song sheets, project booklets, programmes and catalogues, photographs, and CD Roms. I now turn to an example of one such CD Rom.

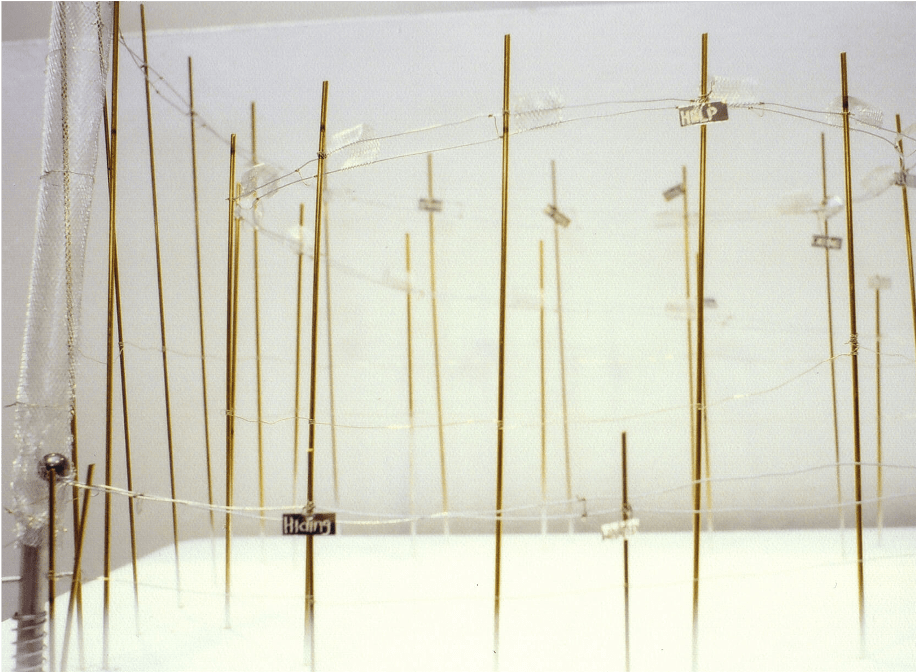

In 2002, Rideout delivered their first cross-artform project, Repeating Stories. Working with artist and sculptor Jon Ford, the project was a blend of drama, drawing, and 3-D art making. It supported participants to create ‘kinetic sculptures’ that represented repetitive behaviours and contexts that brought them into prison. The project involved residencies at 3 different prisons in Staffordshire and culminated in public exhibitions at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre and the Burslem School of Art.

Rideout created a CD Rom of the project to collect together the varied materials emerging from it, including: original designs, audio of the participant talking about their sculpture, movies of the sculptures on show in a gallery, and audio comments from visitors to the exhibition. As Hewish said, the company made the CD ROM so they ‘could share that with the prisoners because we knew they wouldn’t get to see their work in the exhibition.’ (Bartley Interview, 2023). Participants were able to see images of their work in a public gallery and hear viewer responses to it; further, they were able to that CD Rom with their own friends and family.

So, while the carceral archive that Sutherland identifies seeks to record people in order to reduce them solely to the harmful behaviour they perpetrate and separate them from society; many of the material traces in Rideout’s archive document a persistent attempt to use arts practice to produce reflections and exchanges across the prison boundary.

Even when, as with Repeating Stories, the theme of the project is harmful behaviours, working through kinetic sculpture to express and reflect on why one might repeat harmful patterns, offers a different question or perspective to that present in the State record.

Prison arts archives that illuminate the creative practice of incarcerated people might then, in some ways, contest the dehumanising and reductive material recorded by the state. Such collections have the capacity to contribute to liberatory efforts in resisting the material of carceral archives.

The Carceral Archive and Narratives of Resistance

While Sutherland identifies carceral archives as the expanding material records that might be deployed as evidentiary information used to punish individuals; she also introduces a concept of the carceral archive. This being,

the history and memory of human existence that has been formed by and/or bound to captivity, ownership, domination, control, imperialism, colonialism, hegemony, forced conformity, and white supremacy. The carceral archive is one in which oppressed people cannot escape the historical memory and historical trauma that is codified, reinforced, reinscribed, and reified in the documentary record as part of the work of maintaining dominant cultural narratives.

(Sutherland, 2019)

The carceral archive is a pervasive social and cultural practice that constructs, categorises, and classifies narratives of power and legitimacy.

Focusing on the context of British prison arts, I suggest the notion of ‘public acceptability’ might be a manifestation of one such dominant narrative. So, briefly, in 2008 The Comedy School was required to pull its Stand Up Comedy project at HMP Whitemoor in the wake of a salacious article in The Sun Newspaper titled ‘Are You Having a Laugh’. The tabloid narrative was basically, how can we as a society allow terrorists to participate in a comedy course.

Following the article, then Justice Secretary Jack Straw wrote to all prison governors in England and Wales instructing them ‘to ensure that activities for prisoners are appropriate, purposeful and meet the public acceptability test’, i.e. what is deemed socially palatable activities to be undertaken by those in prison. This moment has become a kind of flash point in the field of prison arts.

Subsequently, the discussion of arts practice in prisons has been persistently erased from public discourse in Britain, largely discussed in sector only or academic settings rather than in wider public celebrations of the nation’s cultural life. So, what does this mean for the prison arts archive? In a context where companies have been cautious around discussing their work in public forums, I suggest the prison arts archive can function as a productive semi-public space in which dominant narratives of The Carceral Archive can be contested.

I am in the process of conducting 30 oral histories of Rideout that will be held in the archive, including conversations with co-founder Saul Hewish, collaborators, board members, formerly incarcerated participants, and peer organisations/artists. In constructing an oral history of Rideout, I am keen to create a space for artists and participants to speak that which can not be spoken in wholly public forums. That is, the oral history is a form which allows a capturing of artists who might not otherwise be documented and articulation of experiences which resist the logic of the carceral archive.

Elsewhere I have reflected on some of the ethical complexities and contradictions of the archive as a bordered site. Here I am interested in the potential of care that might be constituted by that border – that is in protecting these narratives from those that might seek to further stigmatise incarcerated people and undermine arts practice in prison sites. A question I am left with is: Can the archive offer a kind of “managed publicness” that enables a documentation of resistant arts practices but does not expose that practice to the logic of the carceral archive?

Importance of documenting to resist attacks on prison arts in the present

The significance of documenting prison arts is made more acute by the contemporary restricting of what is possible in prisons in England and Wales. Prisons are in crisis, overcrowded, understaffed, and are reeling from an intensification of the privatisation of education and training activities. In this context prison theatre (alongside broader concerns around safety, living conditions, and overpopulation) is under acute pressures.

Hanna Meretoja’s work on narrative ethics asserts that ‘narratives both expand and diminish our sense of the possible’ (2018: 2). Storytelling is a fundamentally world-making process that shapes our understanding, imagination and actions.

The Rideout Archive then, stands as an important resource that recognises possibility of artistry and imagination in prison contexts. The afterlife of prison arts in the archive then can serve an important function in a fight to maintain the possibilities of imagining alternative ways of making, thinking, and exploring in a prison context. As Stuart Hall notes, archives ‘always stand in an active, dialogic relation to the questions which the present puts to the past’.

Some of the questions Rideout’s archive offers include:

- Filmed workshops from The Means of Production, in which Hewish and Johnston are Creative Leadership programme for incarcerated men interested in setting up arts projects on the outside

- A film of Sail or Jail, a large-scale musical performance created in collaboration with The Irene Taylor Trust and the Philharmonic Orchestra with men at HMP the Mount

- Architectural drawings, films, and booklets from The Creative Prison, a collaboration with architect Will Alsop and staff and men held at HMP Gartree, to design a prison that centred rehabilitation and education.

- Recipes and scripts from Past Time, a history, food, and theatre project that explored experiences of prison food across time through a combination cooking classes and theatre workshops.

These projects are a different kind of evidence, an evidence that attests to the possibility of creating audacious, joyful, critical, meaningful work in our prisons. We need that evidence now more than ever.

This text is from a talk I gave at the Theatre and Performance Research Association Conference, on 6 September 2024.

References

Caswell, Michelle. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2021.

Hall, Stuart. 2001. “Constituting an Archive.” Third Text 15 (54): 89–92. doi:10.1080/09528820108576903.

Meretoja, Hanna. The Ethics of Storytelling: Narrative Hermeneutics, History, and the Possible. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Sutherland, Tonia. 2019. “The Carceral Archive: Documentary Records, Narrative Construction, and Predictive Risk Assessment.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.039.

Leave a comment