Below is the text of the talk I gave at the launch of the Rideout Archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection on 30 April 2024.

Rideout Creative Arts for Rehabilitation is one of a set of pioneering British arts and criminal justice organisations established in the eighties and nineties that are still led by a founding member. Over the next decade or so many of these founders are likely to retire, prompting a seismic shift in arts criminal justice practice in the Britain as a change of leadership at these foundational organisations, or their potential closure, alters the landscape of the sector. During my fellowship, I focus on Rideout in order to develop research strategies that attend to this imminent period of change and address the potential erasure of particularly distinctive prison arts that accompany it.

The collaboration with Bristol Theatre Collection as part of the research project has facilitated the creation of the Rideout Archive that we are launching today. And I want to say a huge thank you to Heather, Nigel and the other archivists who have worked on the collection in order to create the first publicly accessible archive of Rideout’s work.

In my talk today, I want to reflect on:

- What actually remains from prison theatre work

- consider the potency of recording cultural activities in a prison context,

- And argue for the vital role of archival practice in resisting the current erosion of the cultural lives of those in prisons.

We’re here to talk about Rideout today, but before them, before even the stalwarts of arts in criminal justice practice Geese Theatre and Clean Break Theatre there was Stirabout Theatre. Stirabout began in 1974 and was the first company purposely founded to take performance into prisons, borstals and detention centres. In their first year the company consisted of four professional actors, a social worker and a drag artist. Fifty years on there has been a proliferation of theatre practice in prisons: flourishing during the alternative theatre movement that continued on into the eighties; the field adapted to the professionalisation of community arts in the nineties and noughties; and increasingly practitioners have been called to navigate the slew of prison policies and media narratives that emerged around prison activities in the 2010s. So, this year, marks 50 years of prison theatre in Britain. It is also 25 years since Saul Hewish and Chris Johnston founded Rideout, making 2024 a significant year in both the history of the company and the wider field. But standing at these landmarks, what remains after fifty, or even after twenty five, years of prison theatre practice?

The histories and distinctive creative practices of theatre practitioners working in British prisons are at risk of being lost if there is not a concerted effort to capture them. These histories are difficult to trace, as the implicit ephemerality of performance is coupled with opaque systems of incarceration and a politically charged reticence of the prison service in England and Wales to publicise arts practices that take place in prisons. Baz Kershaw and Kelly Freebody have separately identified the under-historicisation of applied theatre, the wider field that arts and criminal justice practices sit within (Kershaw, 2016; Freebody, 2018). Further, academic writing on the work of prison theatre practitioners is often limited to single projects that have had a researcher embedded in them, arts evaluations on the effectiveness of companies work against specific metrics, or the writing of scholar artists on their own practice. Companies rarely have the resources to create their own archive and the loss of knowledge about this work becomes particularly acute given the ephemeral nature of prison theatre practices.

So, What Actually Remains?

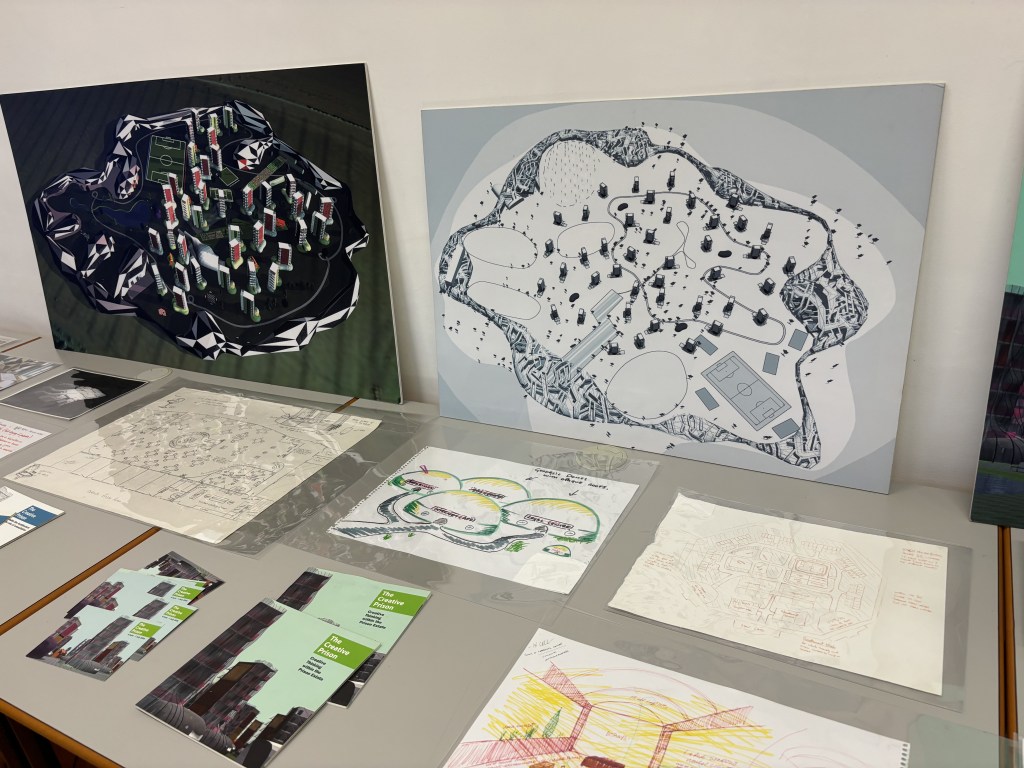

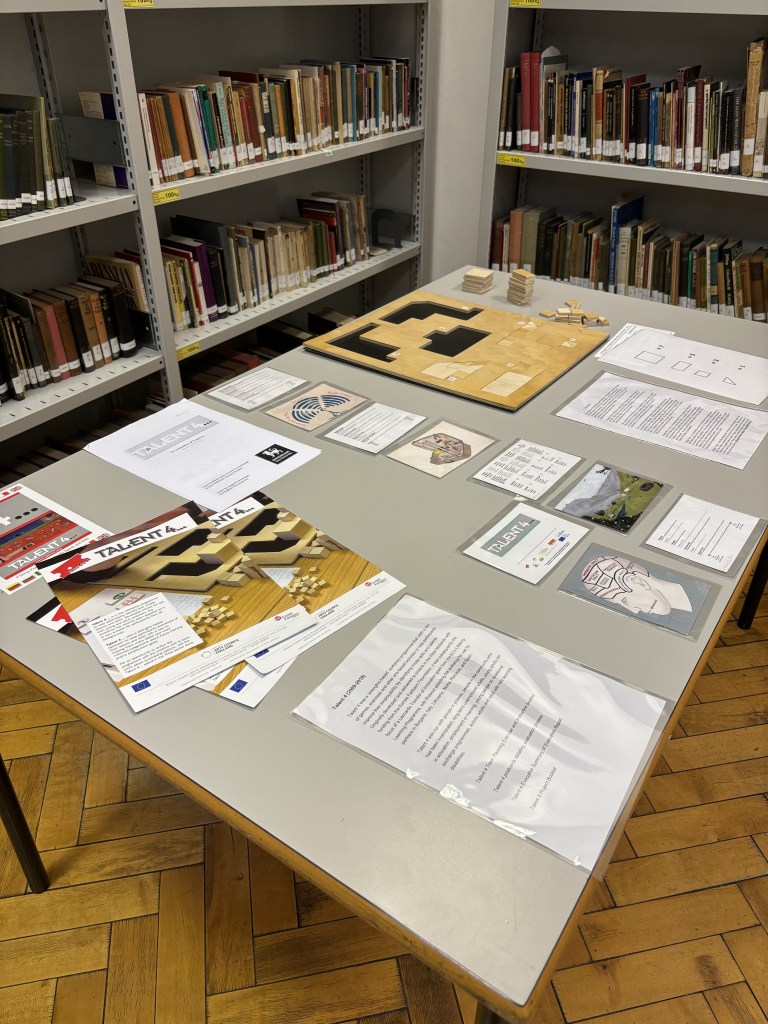

For me, one of the most exciting things about the Rideout Collection is the sheer diversity of material that remains from their work. Board minutes, funding applications, correspondence, scripts, participant work in progress, photographs, films of workshops, films of performances, films themselves, architectural drawings, audio recordings of songs, participatory games, Lego models, and lots of lists! In part, I think, this rich range of material is due to the interdisciplinary and cross artform nature of the company’s work. A cross artform approach is both generative to the creative practice of the company but it also, excitingly for a theatre researcher, leaves different kinds of traces of their work for us to explore.

As part of the research project, I am also conducting 30 or so oral histories with people involved in Rideout’s work. So much of the histories of prison arts practice lives with the artists, participants, practitioners, and producers involved in creating this work. This became acutely clear to me in my work on the Clean Break Archive Project, during which a team undertook around 40 or so interviews with 90 plus women involved in the company’s work. As I noted, there is an opaqueness that surrounds prison arts practice, and ways in which stories have been told about cultural activities in prison in media discourse over the past two decades has been politically charged. Storytelling then, becomes an important practice in the archiving of prison arts and the archive becomes an important home for practitioner and participant stories, which have not so easily found spaces in the contested public discourse around prison and punishment.

- Also check out prison memory archive an inclusive collection of walk-and-talk recordings with those who had a connection with Armagh Gaol and Maze and Long Kesh in Northern Ireland. Demonstrates significance of storytelling as an inclusive practice of prison archiving.

Changing What’s Recorded

The criminal legal system operates through a process of record keeping: statements; transcripts; criminal records; offender assessments; internal adjudications; probation reports the list goes on. The act of archiving, or recording, activities undertaken by people in prison therefore holds a distinctive weight for a community who are persistently recorded, and who may experience record keeping as a form of control. As legal scholars Edward Jones and Jessica Jones note: ‘Contact with the criminal justice system can have a profound impact on an individual’s life and prospects. The state has a long memory and, when coupled with the increasing availability and longevity of newspaper reports and commentary online, it can be difficult for a person to move on from the stigma of a conviction or allegation made against them’. To record the activities of participants in a prison project becomes ethically complex in such a terrain of surveillance.

However, I would suggest that by attending sensitively to the absences of documentation around prison arts practice, then we can contribute to shifting what is recorded about people who are incarcerated. As hopefully some of the material you’ve seen today demonstrates, a prison arts archive can illuminate someone’s creativity, learning, collaboration in ways that are otherwise undocumented or even elided by what is recorded about them during a prison sentence. That is, rather than only recording information in relation to criminalisation and punishment, the archiving of arts practice in prisons offer an expanded representation of what someone in prison might do and be. This could serve to expand the public imagination around those who are incarcerated.

Remembering What Was Possible / Imagining What Could Be Again

Beyond the importance of diversifying what is recorded about people in prison, the significance of archiving prison arts is made more acute by the contemporary restricting of what is possible in prisons in England and Wales.

The living conditions and cultural lives of those incarcerated continue to decline in England and Wales. The prison population has risen by 74% in the last thirty years and it is projected to rise by a further 20,000 by 2026, despite no correlation in rising crime figures. Incidents of violence, drug use, and self-harm are at an all-time high in prisons in England and Wales. Assaults on prison officers increased 24% in 2023; substance misuse has been described as an epidemic by HMPPS; and the number of incarcerated people committing suicide has risen a quarter in the past 12 months. Prisons are overcrowded, understaffed, and are reeling from an intensification of the privatisation of education and training activities.

In this landscape, companies running theatre projects in prisons are facing unprecedent challenges. It’s become increasingly hard to get permission to enter prison and run project; even once inside staffing shortages mean there are often issues getting people into the space to participate; inviting large audiences of imprisoned people to see work made by their peers has become more or less impossible. [REF proStafford].

The spaces of possibility for prison theatre are narrowing and the cultural practices of the last fifty years seem increasingly impossible in the current economic, ideological, and political context of prisons in England and Wales:

In 1979 a group of incarcerated women get day passes to perform their devised revue show for two nights outside of the prison at a local arts centre (Clean Break, 1979);

In 2003 practitioners running a creative leadership course to equip participants to run their own arts projects in a prison (Rideout, 2003);

In 2012 a company running a five-week daily rehearsal period for glengarry glen ross followed by public performances in prison (Synergy, 2009).

If we fail to document the histories of this work we foreclose the imagined possibilities of prison theatre practice in the future, leaving emerging practitioners reliant on the carceral imaginaries of the State. It may seem like it was never possible to…

So we’re fifty years on from Stirabout and prison theatre has been through a lot. We are at an exciting time for the preservation of this practice. Over the past five years, some organisations have begun the process of capturing their histories. Clean Break Theatre opened their archive at Bishopsgate Library in London in 2021; TiPP in Manchester have created a partial digital archive of their 33 years of practice; to celebrate their 20th birthday, Open Clasp in Newcastle did a collaborative archive project with women engaged in their work, the Collection is now held at Newcastle University.

There is an increasingly urgent need for the field to document the histories of organisations and practitioners in order to provide space for alternative narratives from people who come into contact with the criminal legal system and refuse the reductive and singular ways in which their experiences are recorded by the State. Further, such documentation is vital to challenging the increasing degradation of the educational, relational and cultural lives of people who are incarcerated in England and Wales. We hope that the work here at Bristol Theatre Collection will contribute to a wider learning around documenting and sharing the diverse histories of prison theatre practice.

Leave a comment